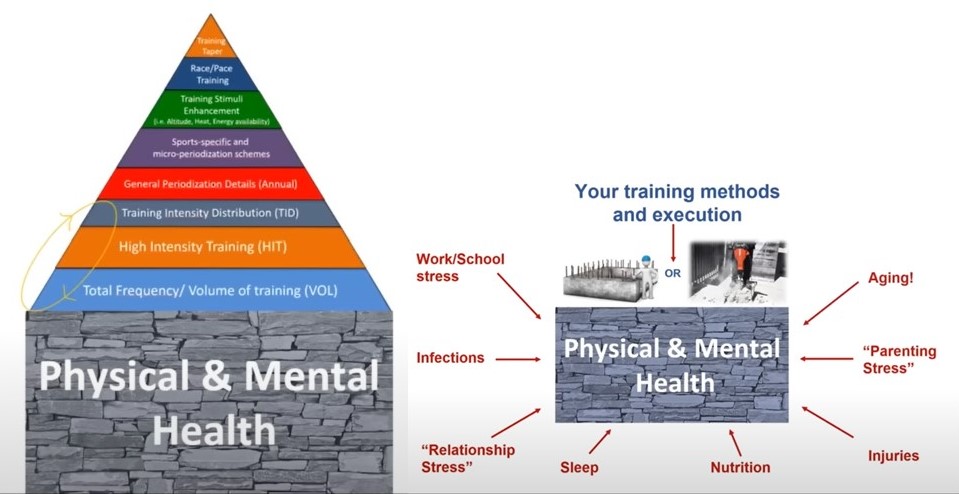

What’s holding you back? What’s keeping your from reaching your goals? You may be doing do all the standard things you’re supposed to be doing – long runs, short intervals, tempo runs, etc. However, are you really addressing the things that are limiting your success?

1: Identify your limiters. Limiters are more than just weaknesses; e.g., speed vs endurance, hills. Such weaknesses are limiters, but there’s a lot more to it. Pause, step back and take a look at your life, your last few racing seasons. Think about the things that have impacted your training and racing.

Make a list. Limiters also include things like:

- Lack of experience.

- Pacing/race strategy.

- Fuel and fluids.

- History of injuries.

- Equipment.

- Work/life stress.

- Sleep.

- Diet.

- Confidence.

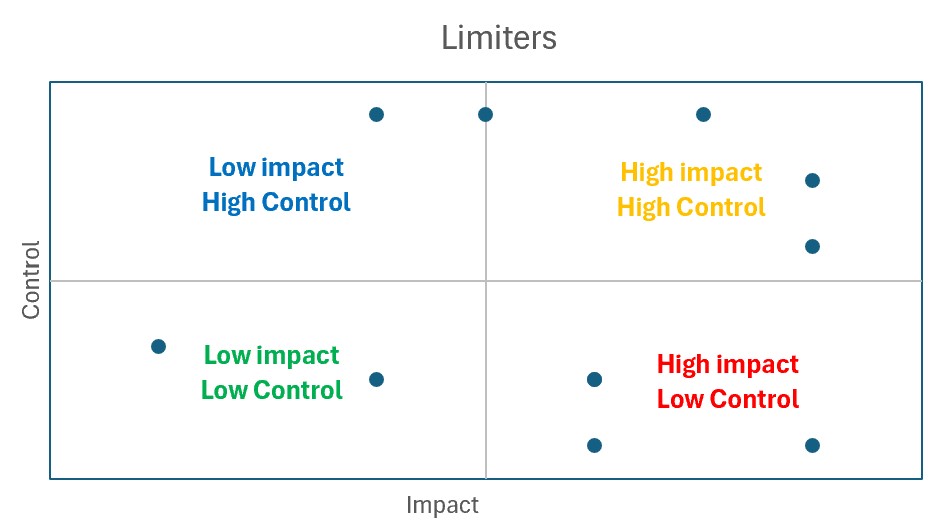

2: Classify the limiters. Think about each in terms of how much it impacts you, and how much control you have over it. Plot them in a chart where impact is on the horizontal axis (high impact to the right), and control on the vertical axis (high control towards the top). You’ll have four quadrants. Ideally, everything would be in the top left quadrant (low impact, high control). Realistically, they won’t be.

3: Identify the ones with the greatest impact on your training and racing. The ones you have high control over (top right quadrant), identify things you can do to change how they impact you.

4: The ones you have low control over (bottom right quadrant), think about how you can gain more control. There are some that are difficult to control. For example, if you have young kids, you know they’re going to get sick, you just don’t know when. Take that into account when you set your goals. Build in more time to account for inevitable interruptions. Be flexible with your training plans, moving and modifying workouts when needed.

I cut way back on my running when my twins were born (family had a higher priority). Once they started sleeping more predictably, I wanted to start running more regularly. It was still difficult to run consistently with their sleep and my wife’s varied work schedule. I started getting up at 4:30am, and would run on the treadmill with the baby monitor nearby. Sometimes I’d have to jump off in response to a screaming baby, but I created an opportunity to run more. I moved something from lower to higher control.

5. Look for ways to exert some control over the issue, no matter how small.

For the last few years, I’ve had some ongoing, fairly high-level, background stress. I hadn’t been sleeping well. Once I recognized that, I backed off on my training; you can only train effectively as much as you can recover. I started meditating regularly. It has lowered my stress levels, allowed me to sleep better, and to train more.

I had a client, training for the London Marathon, who observed Ramadan. That meant she fasted from sunrise to sunset, no food or water. Ramadan ended just a few days before the marathon. This was high impact, low control I only found out about this a week or so before the start of Ramadan. I did some research, then came up with a plan that seemed to work for her. She would get up early, workout for an hour or so, then eat before sunrise. And, she would start her evening runs about 30-minutes before sunrise, carry water and foods, then start to eat on her run after sunset. It wasn’t ideal, but we were able to exert some control over the situation and find a way to make it work. FWIW, Sifan Hassan, the 2023 London Marathon winner, also observed and trained through Ramadan.

Injuries: Consistency in training is more important that the specifics. To be consistent, you have to stay healthy, as well as sleep and recover well. It’s better to undershoot a bit in your training, to stay healthy so that you can train consistently, than to push too far/hard and risk injury. You (should) know your body. You know your history.

I had a client, an army veteran, with a bad back from combat. The client didn’t know when their back would act up. My goal was to keep my client healthy and able to train consistently. So, from day one, we went with a run-walk program. This would reduce the risk of the back acting up. We started with relatively frequent and long walk breaks, and gradually lengthened the runs. For the marathon, I had the client do run-walk from the start rather than waiting for their back to tighten up. This worked. They were able to complete the marathon without having any back issues.

After an injury prone early 2023, and very little running during the latter half, I have set modest goals for 2024, but aggressive ones for 2025. This will give me time to ramp up my training more conservatively and safely. I’m taking days off even when I feel OK, and not running through niggles like I used to. I’m not running to exhaustion on my long runs and speed workouts. I’m cross-training (mainly biking and swimming) to build a bigger cardio engine while limiting the strain on my legs. So far, so good. I’ve stayed injury free and have been improving my fitness. I’m not getting faster as quick as I’d like – I have to remember to be patient – but I’m on a good path towards 2025.

Ignoring history and doing the same things will get you the same results. Figure out what’s really holding you back. Identify, then address your limiters. You may not be able to eliminate them all, but even small impacts can lead to big results.

Train smart. Have fun. Smile. See you on the trails (and roads).

For more training advice, coaching services, and races, visit